BRI Interview Series: Parag Khanna on “The future is Asian”

Parag Khanna

Parag Khanna is a leading global strategy advisor, world traveler, and best-selling author. He is Founder & Managing Partner of FutureMap, a data and scenario-based strategic advisory firm. Parag's newest book is The Future is Asian: Commerce, Conflict & Culture in the 21st Century (2019). He is author of a trilogy of books on the future of world order beginning with The Second World: Empires and Influence in the New Global Order (2008), followed by How to Run the World: Charting a Course to the Next Renaissance (2011), and concluding with Connectography: Mapping the Future of Global Civilization (2016). He is also the author of Technocracy in America: Rise of the Info-State (2017) and co-author of Hybrid Reality: Thriving in the Emerging Human-Technology Civilization (2012). In 2008, Parag was named one of Esquire’s “75 Most Influential People of the 21st Century,” and featured in WIRED magazine’s “Smart List.” He holds a Ph.D. from the London School of Economics, and Bachelors and Masters degrees from the School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University. He has traveled to more than 100 countries and is a Young Global Leader of the World Economic Forum.

Belt and Road Advisory: You have talked about connectivity being the most fundamental megatrend in human history. Can you elaborate on that?

Parag Khanna: The one constant in human activity over the millennia is that with whatever technologies we have available to ourselves, whether it’s stone tools, high-speed railways or fiber-optic internet cables, people use those technologies to connect human societies to each other. The principle unit that is being connected is not the politically bordered state, but instead the city.

Cities we have had for seven thousand years, empires for a couple of thousand years, modern nation states only a couple of hundred years. Empires rise and fall, countries come and go, but cities are truly eternal. That’s why I argue that connectivity between cities is the most fundamental megatrend in the world and its accelerating all the time.

However, increasing connectivity does not necessarily mean its peaceful. There is a competitive dimension and that’s where the contrast between political borders and connective infrastructures comes in. It's not that one is necessarily superseding the other, but it's that one transcends the other. Today there are more borders and sovereign units than ever before, and new secessionist movements are seeking to lay down even more borders. But the bigger and longer-lasting trend is that we are actually building more connective infrastructures across those borders.

We have about five to six times more kilometers of global infrastructure connectivity – including railways, pipelines and highways than we have borders. The amount of connectivity is far greater than political division and yet we don't map the former. So, to have maps only encompassing political geography defined by borders is inadequate to explain the world. Instead, we need to look at functional geography which include connective infrastructures.

We are also seeing competition over this connective infrastructure due to its tremendous value. The networks of stock exchanges, railways, oil and gas pipelines among others have a huge financial value, connote political leverage and bring about new dynamics across countries. So as much as these infrastructures can promote comparative advantage in economic terms and optimize distribution of resources, they actually become more important than borders and carry significantly more value.

Belt and Road Advisory: China, with its Belt and Road Initiative, is a key player in global connectivity. What is your take on the Chinese strategy towards connectivity?

Parag Khanna: The Belt and Road fits into a longer pattern of global infrastructure build out. It was in the late nineteenth century that America took the lead in infrastructure investment, then Europe after World War II. After that, Asia took center stage with infrastructure buildout. It started in the 1960s and 1970s with Japan, South Korea and then of course China in the 1990s. The 1990s is a critical period to reflect on the beginning of Belt and Road as that was when we first saw Chinese construction companies expanding internationally.

I have spent much time in the last 25 years since the collapse of the Soviet Union traveling in the former Soviet republics of Central Asia. That was when I began to see that China was making significant infrastructure investments in its neighbor countries like Kazakhstan. So, in my mind, Belt and Road has been happening for a quarter of century.

Only in the last five years, when this phenomenon acquired a new name, a new acronym and became a multilateral enterprise have we started talking about this as the largest coordinated infrastructure investment campaign in human history. BRI is very significant because infrastructure has historically tended to be something that's domestically focused, done through government spending. But we now have many countries collaborating in their infrastructure development. It's certainly multi modal and covers transportation, energy, communications many other areas. It’s not just publicly financed either – yes Chinese public funding has provided a jolt of support to BRI – but it is multilateral as it is beginning to include the world’s biggest financiers who are seeking to tap into BRI. This includes both private financiers and other multilateral development banks.

In the last five years, BRI has not only seen a big start rhetorically, but also in terms of the volume of capital that is being committed. Of course, there are both pluses and minuses to the Chinese approach. As we have seen, some projects have stalled as a result of rising costs, financing debt among other reasons.

But generally speaking, from the projects I have mapped out and visited, I expect that the vast majority of them will move forward because they are designed through a mutual and collective decision-making process based on the needs of the recipient country. Many of these BRI countries are small, poor and frail post-colonial countries whose populations have tripled or quadrupled, and they lack basic amenities like reliable electricity supply and good roads. There is a need for more and better infrastructure to cater to these demands; and yes, while there will be some projects that stall, get renegotiated or cancelled, the aggregate picture is one in which the BRI infrastructure moves to completion and satisfies a growing need.

Belt and Road Advisory: Critics often argue that BRI is a geopolitical ploy through which China can exert its influence around the world. What’s your take on that?

Parag Khanna: Well a cross-border infrastructure investment, for example, a railway or a port cannot be taken back later down the line. It becomes a structural part of an economy’s backbone. For the Chinese, building infrastructure across Eurasia to reach the Caspian Sea, Persian Gulf, Eurasia and even the Arctic provides a structural solution to evading the Malacca Trap. The Malacca Strait choke point is a nineteenth century geopolitical dilemma and therefore from a Chinese strategic standpoint, it is a very legitimate priority. While solving the dilemma, they can elevate poorer countries into global value chains through the provision of infrastructural public goods.

Something can be strategic and a public good at the same time. So, there is not necessarily a tension between those who view Belt and Road as a political exercise and those who view it as something that's a part of economic modernization for underdeveloped countries. It is both at the same time and there's nothing wrong with that. So I think everyone needs to get that reconciled in their understanding.

On the point that BRI cements Chinese influence in these countries. We don't live in the world of the seventeenth, eighteenth, nineteenth centuries when European empires simply marched into foreign countries with their guns, tanks and troops and simply conquered them; turning them into political colonies that lasted for centuries.

We live in a world of sovereignty, of transparency, and of democracy in many of these countries. What we have already seen in the last few years is that countries have a right to say no to BRI, they have an ability to renegotiate. We have already seen that in countries like Malaysia, Pakistan and Myanmar. So the colonial analogy is a false one.

Interestingly, Chinese investments in these countries may diminish Chinese influence over the long term. What history shows us is that Infrastructure is the most essential foundation for national modernization and economic development; it will catalyze economic reform and encourage economic diversification. In turn, these countries will become more attractive to other non-Chinese investors. As they do so, the Chinese share of investment in these countries will go down and so will their leverage, diminishing Chinese influence.

Belt and Road Advisory: Your next book that is coming out early next year, titled: “The Future is Asian: Commerce, Conflict and Culture in the 21st Century.” Can you share with us some of the key hypotheses that you're going to be making in this book?

Parag Khanna: One of the reasons for writing the book was to point out that Asia is more than just China. Now that's an important message for western audiences and for western businesses who have been very rightly focused on China over the last twenty years. It's also a message for Chinese people to get to know the rest of Asia better.

I wrote this book with both purposes in mind; to educate the West about Asia and to educate Asians about each other. Because really, my point of departure is that Asian nations and civilizations have not had much interaction with each other over the last 500 years because of colonialism and the cold war.

The Asian system that existed in the sixteenth century; a thriving, robust network of trade spanning the Arabian Peninsula to Central Asia, through India, Southeast Asia and China was splintered and Asians began to turn inward during colonization. They had more significant relations with their European colonial masters than they had with each other, and only now in the past quarter of a century through the opening of Asian economies are we seeing the return of Asia as a system again. Asians now do more business and trade with each other, and interact more with each other, than they do with Western powers on a daily basis. The resurrection of the great Asian system is what this book is about.

Belt and Road Advisory: What’s your view on the US-China trade war? Who will win?

Parag Khanna: This is a bilateral dispute and has global implications, but it doesn't mean that those implications are all negative. In fact - as with real war - in a trade war, the winner is usually not one of the two: protagonist or antagonist. It's usually a third party.

And that’s already what we are seeing with the US-China dispute. You have Europe trying to edge out the United States in exporting goods to China where American goods are becoming more expensive because of retaliatory tariffs. At the same time, you have a diversion of production from China in certain industries to Southeast Asia. Vietnam, Indonesia and the Philippines are beneficiaries. So I can identify several winners from this trade war that are not America or China; instead they are Germany, they are Vietnam, they are the Philippines and Thailand.

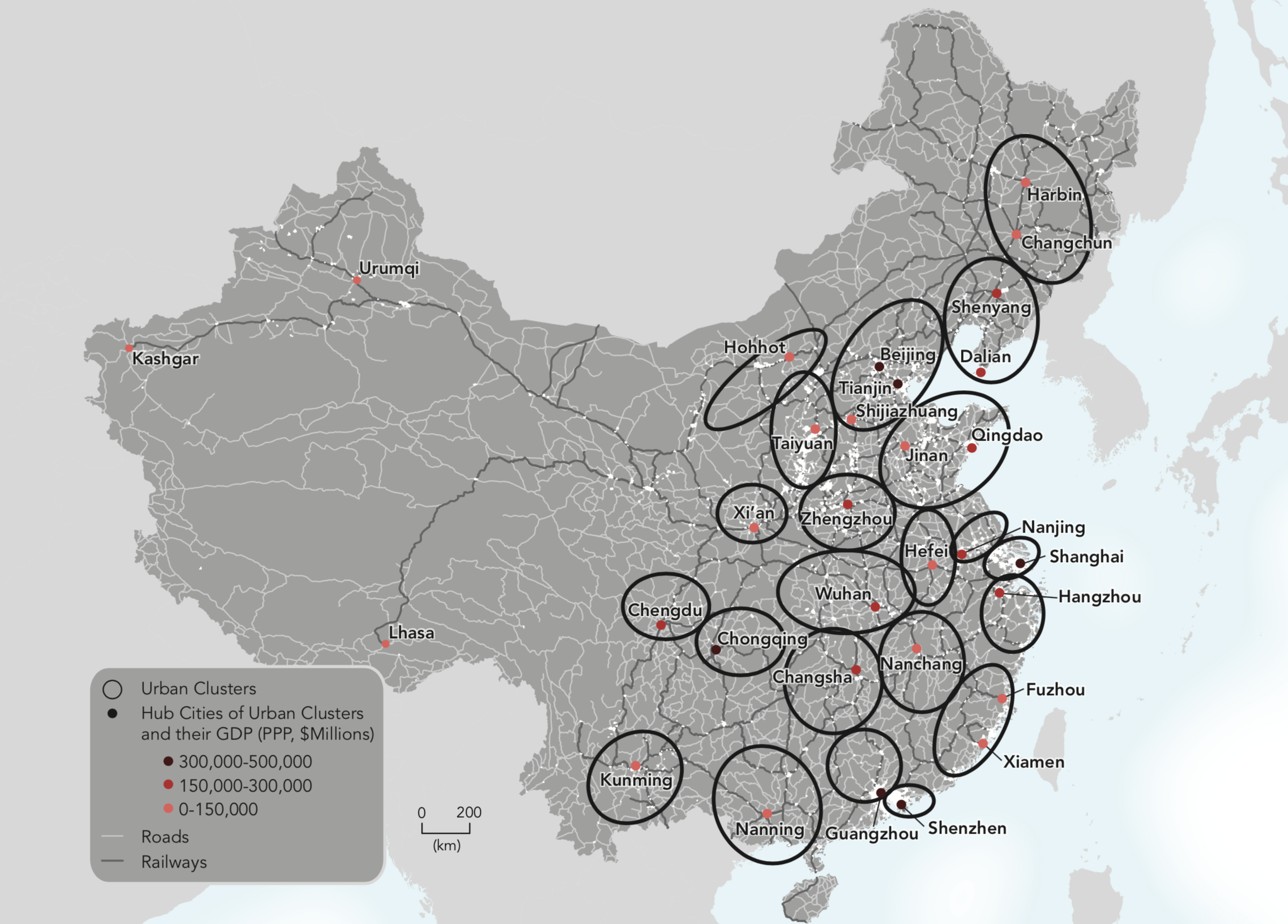

See some of Parag’s amazing work below. These maps show why cities will play a crucial role as connectivity hubs and why the future is Asian.