Is China taking over Central and Eastern Europe? – Fact Check

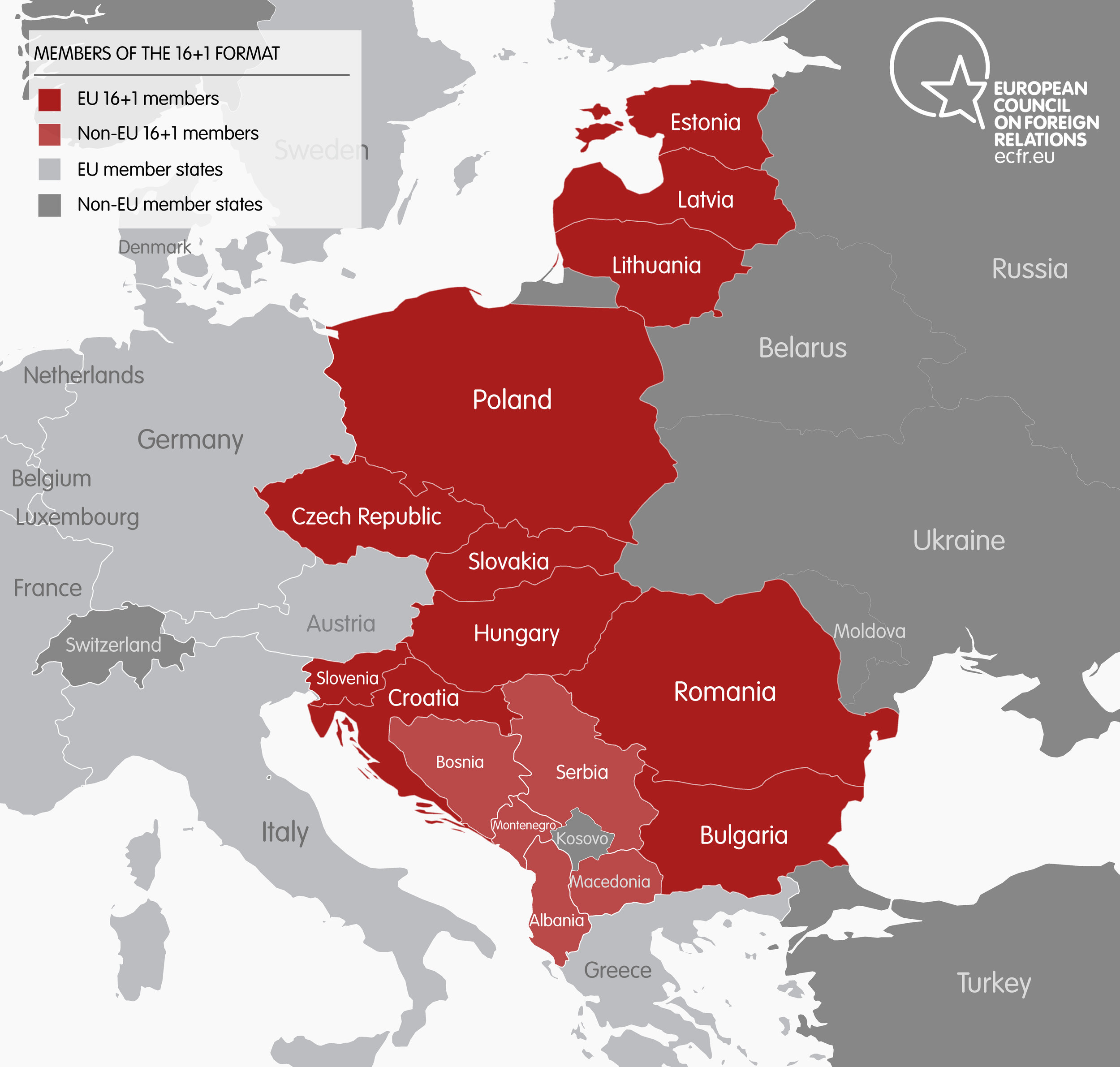

The sixth 16+1 China-Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) Cooperation Summit, this year held in Budapest, came to a conclusion on November 27th. Established in 2012 and related to Belt and Road Initiative; the 16+1 platform connects China with 16 CEE countries. This year, the headlines focused on Chinese Premier Li Keqiang’s announcement of $3 billion of additional financing for CEE, which complements an $11 billion fund already announced. The new financing mechanisms include the China-CEEC Inter-Bank Association, which has received funding of $2.39 billion from the China Development Bank. Moreover, the China-CEE Investment Cooperation Fund was moved into its second stage with another $1 billion.

16+1-MEMBERS.jpg

As in previous years, the announcements triggered a renewed discussion about the tensions between China, CEE, and the EU. The EU’s fears originate from China’s growing economic presence in 16+1 countries and the corresponding geopolitical leverage those investments may command. As 11 of the 16 CEE countries are EU members, these countries are seen by Brussels as vital for ensuring EU’s united stance towards China.

In a previous piece, we looked at the Belgrade-Budapest High-Speed Railway as a key example of tensions in the China, CEE and EU triangle. In this piece, we examine three oft-cited claims on the triangle: (1) on China’s aggregate economic presence in CEE, (2) its capacity to influence CEE countries, and (3) the potential of CEE to become a united Eurosceptic group closely tied to China.

Claim 1: China has a strong economic foothold in CEE

The primary assumption behind the EU’s concerns is that China has a significant economic power base in CEE. This perception is fuelled by impressive announcements made during 16+1 Summits or MoUs signed during bilateral visits. Despite this, the data tells another story.

Many of the Chinese financing mechanisms are not attractive for the EU CEE states which enjoy access to the EU Cohesion Fund; a fund that does not come with the requirement of using specific Chinese contractors. Interestingly, Chinese offers of investment have been repeated at 16+1 Summits at least since 2014, yet the actual amount deployed is minimal.

Similarly, MoUs often are an important show of political will, but seemingly not a catalyst for action by Chinese investors. For instance, during President Xi Jinping’s visit to Prague in March 2016, it was announced that the Czech Republic would receive over 3 billion EUR worth of Chinese investments by the end of 2016. However, by December 2017, little progress, if any at all, had been made.

Trade and investment relations show a similar picture – realities on the ground do not reflect the announcements made at major summits. While China-CEE trade grew rapidly prior to 2012; increasing from 32 to 52 billion USD between 2009 and 2012, the pace of growth has significantly slowed in the last five years. By 2016, China-CEE trade had only reached 58 billion USD, far below the target of $100 billion outlined by Premier Wen Jiabao in 2012. With regard to Chinese FDI, it is not as all-encompassing as many assume. Firstly, around 95% of Chinese FDI in CEE go to six countries - Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania, and Slovakia. Secondly, Chinese FDI comprises only a small part of the overall FDI in these countries. For instance, Poland, a country which on its own comprises 45% of the GDP of CEE, received less than 0.01% of its total FDI from Chinese sources in 2015. And even in the case of Hungary, the leader among the recipients of Chinese FDI in the region, Chinese FDI amount to around 1% of the overall total.

Claim 2: China can use its economic presence in CEE as political leverage against EU

This claim has gained weight ever since Hungary’s 2016 opposition to an EU statement criticising China’s actions in the South China Sea with Croatia and Slovenia being reluctant to support strong criticism, as they are involved in maritime disputes of their own. Hungary also offered its support for granting China Market Economy Status during the same year. However, beyond the example of Hungary, CEE countries in the EU have not explicitly supported Chinese positions.

Moreover, in large projects, China realises it has to respect EU rules, as was the case for the Belgrade-Budapest Railway. In this case, even though Chinese financiers and their Hungarian partners wanted to keep bidding closed and non-transparent, ultimately they had to abide by EU regulations and adopt an open and transparent process. The recent EU Commission announcement to harmonise FDI screening will also make it harder for China to potentially “purchase” any political favours from CEE governments through its investments. This, in turn, is complemented by the European External Action Service within the 16+1 framework; this acts an enforcement mechanism to prevent foul play and disregard of EU rules.

Claim 3: 16+1 can lead to creation of a united Eurosceptic and China-backed CEE

United and looking towards China in a favourable manner, the 16 (or its 11 EU members) could be a considerable source of political influence in Europe.

However, the reality is there is lack of will to engage in extensive cooperation across the region; as shown, for instance, by the Visegrad Group. This body, which includes the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia has so far failed to engage in any meaningful cooperation.

Rather than being a framework for the united cooperation of the 16 towards China, 16+1 is instead a coordinated set of bilateral relations between China and single states coming from four sub-regional groups (the Baltic States, the Visegrad Group, Post-Yugoslavian states, and Bulgaria and Romania) . Yet, the framework is tangled in a competition of the 16 (particularly between its most influential members – the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Poland) for the ambiguous titles of “leader of the 16+1” and “the gateway to Europe”. Up to now, there have been no significant projects which span across the region, with many countries proposing their own projects, whether it be the Czech concept of the Danube Channel or Polish idea of Via Carpathia.

Nonetheless, even though the threat of a united CEE stance against the EU lacks credibility for the aforementioned reasons, we may see more CEE countries playing on the fears of the EU and attempting to use the perception of rosy relations with China as leverage in dealings with Brussels.

China-CEE is coming, but it is not as dramatic as you think

While trade and investment links have grown over the last decade between China and CEE with Chinese FDI doubling in the region between 2010 and 2015, growth has not hit targets or met expectations of the CEE countries. The framework is set for further developments and there is potential for going forward, but we need to take announcements and MoU’s with a pinch of salt. Similarly, it is hard to imagine China gaining substantial political leverage over CEE EU members, as the EU will no doubt remain the main stakeholder in the region. Moreover, Brussels has a number of accountability mechanisms to keep CEE members in check and that will limit China’s ability to influence these nations.

Hence, in conclusion, at least into the foreseeable future, the 16+1 is likely to remain a platform for CEE countries to compete for Chinese investments but not much more than this. It is hard for CEE countries to adopt a united stance towards Brussels, let alone attempt a strategic rebalancing towards China. Instead, each of the countries is likely to move in a cycle of high hopes and reality checks in their relations with China and stay focused on the politics of the European arena.

Thus our analysis points to the three claims being at best exaggerated, at worst unfounded. Having said that, 16+1 has been successful in constructing political and institutional foundations for future cooperation; so we cannot rule out the possibility of the claims strengthening over time. Our current assessment is one in which neither China’s overly-enthusiastic announcements, nor the sometimes Orwellian EU depiction, accurately reflect the realities of China-CEE cooperation. The reality is, it probably lies somewhere in between.