How Can Your Company Access Belt and Road Funding?

This article will:

Introduce the available sources of BRI financing;

Show you a case study of how a Chinese funding was acquired for an impressive European project;

Tell you how to attract Chinese investors through developing your own “BRI brand”.

The magnitude of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) captures headlines all around the world Some estimations say that by 2030 as much as 2 trillion USD will be invested in BRI projects worldwide. Many governments and companies would like to access those BRI funds, but how to do so remains unclear.

So where does the BRI funding come from and how can you access it?

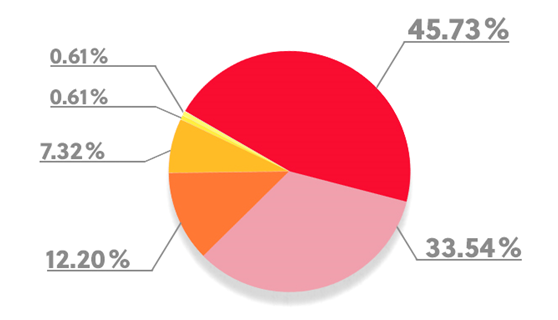

Key Institutions Providing BRI Funding

Source: Belt and Road 101

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the vast majority of BRI financing is Chinese finance. Foreign investors are increasingly looking for ways to jointly finance BRI projects, but up to now, their participation in the initiative has been limited. That’s partly because foreign investors do not have the appetite to invest in some of the countries BRI is focused on, but also because the Chinese side have expressed little desire to engage foreign capital. That may well change with time, and we continue to keep a close eye on the matter. But the fact remains, that BRI is dominated by Chinese financiers and contractors.

Key financiers in China’s BRI

Policy banks: China’s three policy banks, created in 1994, are state-funded. They are development financing institutions with funds allocated both at home and abroad. In particular, two of these policy banks, China Development Bank (CDB) and Export-Import Bank of China (CEXIM) and have significant capital allotted for infrastructure projects overseas. To give an idea of size, their combined total assets exceed the cumulative sum of all the Western-backed development banks combined. These policy banks do not suffer from the same capital constraints as the Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs), as they can tap into the extensive foreign reserves held by the Chinese government (approximately $3 trillion) and are heavily focused on infrastructure and related activities. Moreover, they can raise finance easily through debt markets at low interest rates given the fact that they benefit from an implicit state guarantee. They have long time horizons, and often offer loans at concessional rates for the largest BRI projects.

One of the advantages of working with Chinese partners also can provide is the joint offering of both financing and contracting. Chinese engineering and construction firms have become technically very competent through scaling up their operations at home and abroad; and moreover choosing to work with them also increases the likelihood of securing financing from one of China’s policy banks. Chinese policy banks give preferential treatment to projects using Chinese contractors; in part due to the reduced perception of risk and increased confidence in project completion.

China’s commercial banks: China’s commercial banks also have some funding available for overseas infrastructure projects, albeit more limited. While both the major commercial banks and policy banks are state-owned, the policy banks take on large economic development projects. The commercial banks take on deposits and operate more like retail banks, and need to make a return on their investments.

Chinese local governments: There exist a number of Chinese provinces that are actively seeking to support their firms expand operations from China and move production to countries where labor costs less. The advantage of partnering with Chinese local governments is that they may help to support investment promotion and encourage their firms to relocate. This was the case in the Ethiopia-Hunan SEZ where Changsha Foton, Hengyang TBEA, Hunan Chang Gao, SANY Heavy Industry and other leading enterprises from Hunan have offered their support for the SEZ.

Silk Road Fund: The Chinese government has created the Silk Road Fund with total capital of $43.5 billion to explicitly support BRI projects. The Silk Road Fund aims to make investments that improve trade between China and its neighbors, especially in Central Asia. Its first investments were concentrated in the hydroelectric sector in Pakistan in order to strengthen the Sino-Pakistani economic corridor, an element of the OBOR. More recently, the fund has been looking at Uzbek oil and gas projects.

The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB): The AIIB is a multilateral development bank headquartered in Beijing and operational since 2016. It has authorized capital of $100 billion and supports infrastructure investments. However, in comparison to the policy banks, its available capital to spend each year is smaller – in the region of $3 to $5 billion annually. The bank also has much more stringent approval processes, and operates more like an investment bank seeking to make profit, which limits the countries and sectors it can work in.

Panda bonds: Panda bonds are those issued in renminbi on the Chinese mainland. They can be issued by the developing country government for general financing or for a specific purpose. Given an increasing proportion of developing countries’ trade and investment is denominated in RMB, it may make sense going forward to diversify borrowings and tap into the Chinese debt market. Poland was the first European country to do this in 2016, and the Philippines became the first Southeast Asian nation earlier in 2018.

Private Chinese capital: We’re still in the early stages of China’s private companies internationalizing and participating in the BRI. However, since the BRI became enshrined in China’s constitution, it has become increasingly important and urgent for all companies in China to develop their BRI strategies, including private ones. They don’t have as much experience as the big state backed construction giants who have been operating abroad for decades, but are quick to learn. Already we see the likes of Alibaba pushing their internationalization strategies.

Build your BRI brand, tap into Chinese finance: The case of FinEst Bay

Peter Vesterbacka, a former executive of Rovio, the company behind the world-wide famous mobile games series Angry Birds, is spearheading efforts on an urban infrastructure project called FinEst Bay. Led by a consortium including Poyry and AINS Group, the project will link the capitals of Finland and Estonia - Helsinki and Tallinn. Currently the two cities are connected with a ferry connection that makes the journey time at around 100 minutes. Upon completion of the FinEst Bay, the two cities will be connected by an undersea train that would limit the commute time down to a mere 20-30 minutes.

FinEst Bay Project

Source: Belt and Road 101

While the project received approval from the Finnish government, the €15 billion funding remains an issue and construction has not yet started. As a result, Vesterbacka has looked to Chinese funding, clearly linking the FinEst Bay project with the Belt and Road Initiative and offering as much as 70% of the project to Chinese financiers. In fall 2016 Vesterbacka came to China for an 8 weeks in order to better understand Chinese culture and develop personal relations with his business partners. This combined with Belt and Road branding clearly worked, as in March 2018 the consortium behind the project claimed “to be months away from breaking ground on the project, thanks to unnamed Chinese investors” and Vesterbacka plans to meet the project completion date of December 2024.

“This project is perfectly aligned with China’s Belt and Road Initiative. It’s obvious that there would be big interest from China to connect with Europe, and we happen to be the closest neighbor of China in Europe.”

To access BRI funding, you need to develop a BRI brand for your project. In the case of the FinEst Bay project outlined above, its motivations and objectives align with the BRI. It is focused on infrastructure, has government approval and is also important for the Polar Silk Road (PSR). The PSR is an integral component of the BRI and runs from China to the Arctic; Vesterbacka is acutely aware of this and as such has played on it in his attempts to secure Chinese financing. While negotiations between Vesterbacka and the Chinese are still underway, the fact that they are even happening speaks volumes for the way the project was branded and framed as fitting into the broader objectives of BRI.

Another example is DHL, a global logistics player that seeks to tap into BRI. DHL has developed promotional materials in which it has positioned itself as a key player in the BRI。

DHL’s BRI Brand Materials

Source: DHL

You can apply a similar approach. Analyse the trends in Chinese investments in your sector - be it infrastructure, agriculture or tourism (see Belt and Road 101 for examples) and then develop your own BRI promo materials showing how your activities fit into the Belt and Road Initiative and explain what role can your company play within BRI.

Through framing your project as fitting under the BRI, coupled with strong Chinese partners who can make the right introductions, you will have made the first step in securing BRI financing.

At Belt and Road Advisory, we stand ready to support you build your BRI brand and leverage it to secure financing.

Photo credit: MarTech Advisor

Click here to get a free copy of “Belt and Road 101”, a report introducing the Belt and Road Initiative to business.

*

This article is part of “China-EU BRI Business Series” released by the Belt and Road Advisory

in cooperation with the Benelux Chamber of Commerce